This article was originally published in the December 2001 issue of Motorcycle Cruiser.

Big twins grab the headlines, but middleweights provide comparable performance and function at a fraction of the cost.

The landscape in the 800 V-twin class has changed since we last assembled the players in our August 1997 issue. New entries have arrived and one has departed. There is a wider range of choices now. Prices have dropped, too, making these middleweights even better bargains. It was time to remind ourselves that although V-twin cruisers in the 700cc-900cc range live in the shadow of the over-1200cc machines, the biggest difference is in perception and price. Some great machines and terrific bargains live in this overlooked middle ground.

We began our rediscovery of the middleweight V-twins by surveying what was currently available for our comparison. Last year, Kawasaki added the Drifter to its two existing Vulcan 800s, the 800A and Classic. Since the A-model and Classic are very similar, we only included the Classic, which when the venerable Vulcan 750 was included, gave us three Kawasakis for our comparo.

This year, Honda introduced the street-meanie-style Spirit, which we signed up along with Honda's 750 A.C.E. V-twin. Suzuki also introduced the Volusia for 2001, bringing the count of cruisers powered by its 800 V-twin to three. Since they are distinctively different, we included all three, the others being the Intruder and Marauder.

For 2002, Harley rolled out an additional version of its 883, the dirttrack-style 883R. Although it wasn't our first choice, Harley wanted us to include it instead of one of its more mainstream cruisers. And this time around there is no Yamaha. The firm discontinued the Virago 750 for 1998, hoping that buyers would see the more contemporary V Star 650 as competition to other firms' 800s. Readers have indicated that they don't see the V Star as an 800 alternative, and we don't either.

Though we would have had plenty of opportunity to use them for daily transportation and for weekend rides, we decided to gather all nine bikes for a three-day cruise up the California coast. We planned to use the coast and Cambria as a backdrop for our photos, but coastal clouds pretty much blacked-out that idea. Still, three days in the saddle is always welcome, and we were soon picking out bikes to pack on.

Choosing one of these 800 twins for a long ride will make you think about your priorities. Are you after luggage capacity, comfort for yourself and a passenger or highway power--or some combination thereof?

Pack Your Bags

There is a range of packing capacities within these nine bikes. The Drifter, with its solo saddle and a rear fender that moves with the swingarm, leaves a tank bag or a backpack as your only option for toting stuff. The remaining Kawasakis, on the other hand, have pillion saddles and bungee-cord anchor points. The bikes with dual shocks (Harley, Hondas, Kawasaki 750 and Suzukis) permit you to sling saddlebags on the back end (our Intruder was actually delivered with accessory soft bags) and ride off. Those twin-shockers, such as the Volusia, with the rear turn signals set back at the taillight, make it easier. The ability to pump up the Vulcan 750's rear shocks makes it easy to accommodate the added weight of a passenger or luggage. The small passenger backrests on the Intruder and Vulcan 750 also help secure luggage. Our photographer, who had a variety of gear that wouldn't all go in a saddlebag, selected the Vulcan 750 to pack on. The Volusia was judged the best bet if you had saddlebags.

If comfort is your top priority for a traveling twin, look at the saddle. The big solo saddle on the Drifter was a favorite, but the Volusia saddle was virtually as roomy and also permitted you to take along a friend. These two bikes were top-ranked for comfort, thanks not only to their seats, but also their compliant suspensions, comfortable riding positions and lack of vibration. The Drifter had an edge in legroom and because of its floorboards. Those who felt it presented less wind forces to deal with preferred the Volusia. The A.C.E. was also rated strongly in third place for all the same reasons, though it isn't quite as roomy as either of the other two.

In terms of comfort, the other two Kawasakis occupied the middle of the pack. No one had serious complaints about the Classic, but its riding position wasn't quite as well received as the others. The VN750 has a very smooth, compliant ride and is vibration-free but lost points for its tall, narrow handlebar bend, which felt awkward, and for its seat, which some riders said was cramped. Vibration and rough rides were the main complaints lodged against the Spirit and Sportster. The Spirit buzzes; the Sporty shakes. The Spirit also felt cramped, and its seat chafed all but smaller riders. It did provide the easiest reach to the ground, though. The Sportster's low, narrow handlebar and leaned-forward riding position proved popular at high speeds and when the road began to meander. However, it wasn't a real cruiser posture, and it felt cramped to some. The racy-looking saddle was surprisingly comfortable--more comfy than those of other H-D 883 models--but still too firm after a few hours.

Our Intruder came with an accessory seat, which certainly raised its comfort quotient compared to the narrow, thin stocker but couldn't make up for the uncomfortable position created by the pullback handlebar. The Intruder's engine, which like the other Suzukis, counters vibration by rearranging the power pulses with offset crankpins, was smooth. But bumpy roads were less comfy than with some of the other bikes. The Marauder was judged the least comfortable for its saddle, ride, rider position, mild vibration and lack of compliance over bumps. If you want to bring a passenger, you aren't likely to choose the Drifter. The Sportster, Spirit, Marauder and stock Intruder (despite its backrest) are only marginally better. Our passenger felt a bit confined on the Vulcan 750 but liked the backrest. The A.C.E. and Classic were rated as acceptable for long rides, and the Volusia, which had the most room, was the favorite.

Got Juice?

You can't rely on appearance to judge which one of these bikes will deliver power and performance. The racing lines of the 883R speak of speed, but the Sportster was the slowest bike of the nine. Out on the road, it frequently got left behind when we were traveling fast or passing traffic uphill. It also shook pretty hard when the throttle was open wide.

You might also expect the street-rodded Spirit to hit hard when you goose the throttle, but it also proved to be something of a laggard, just marginally faster than the laid-back-looking A.C.E. All three of these bikes turned in rather leisurely quarter-mile performances--in the mid-15-second range with terminal speeds in the low-80-mph bracket. The lower gearing of the Spirit did help it slightly in our roll-on acceleration test, where we start at 50 mph and see how fast the bike gets going in 200 yards. This is an indication of passing performance. The 70.1-mph top-gear-acceleration speed attained by the Spirit beat not only the A.C.E. and Sportster, but also the two Kawasaki 800s. Most riders said the Kawasaki 800s felt faster, because they accelerate harder through the gears and aren't spinning as hard at a given speed on the highway.

The Volusia was given the same subjective power scores as the two Kawasaki 800s but was actually a tick slower through the quarter-mile. It did deliver significantly more juice than the 800 Vulcans during top-gear acceleration, making it more effective on the open road. Its stablemate, the Marauder, fulfilled its tough-guy image better than the Spirit did. Although the 800 Classic was a hair quicker and faster through the quarter-mile, the Marauder was third best in top-gear performance.

The real powerhouses in the 800 class don't wear their performance, they just deliver it. Maybe it's because they were created in an age when the Japanese felt performance was critical, but the Vulcan 750 and Intruder 800 run away from their classmates. They were the only ones that laid down quarter-mile times in the 13-second range with terminal speeds over 90 mph. They were also the only ones that got into the high-70-mph range in our top-gear-acceleration test. The Intruder is a real powerhouse, thanks not only to its strong power but also to its gearing, which is lower than most of the others. Few big V-twin cruisers can hang with it. In fact, in our last big twin comparison, of the 10 bikes tested, only the Suzuki Intruder 1400 out-sprinted the Intruder 800 through the quarter-mile, and then only by three hundredths of a second and one mph. And don't ignore the stodgy-looking Vulcan 750, which though a couple of tenths slower than the Intruder 800, actually had a higher terminal speed than either the 800 Intruder or its big, bad 1400cc brother. Out on the road, that kind of power translates to quick passes and immediate response when you squeeze the loud handle.

Other aspects of drivetrain performance were less defining. Some riders had trouble with the Harley clutch, feeling it engaged too abruptly. A few said that the Suzuki clutches, particularly the Intruder's, weren't as nice to work with as the others. The Hondas were rated as the top shifters, and the Kawasakis' automatic neutral finder was praised by some. The heel-toe shifting of the floorboard-equipped Drifter was praised or panned by those who either liked it or had trouble adapting. The Volusia shift mechanism sometimes seemed to have trouble re-indexing after a downshift, which was noticeable when you were trying to make a quick series of downshifts. The Harley's gearbox was a bit stiffer and noisier than the others, though no one missed any shifts with the 883R. It also has the tallest first gear, requiring more clutch slipping (with the heaviest clutch pull) than any other bike to make a quick departure.

What You See

Our stay in the Cambria area included a visit to Hearst Castle, a bit of seal watching along the coast and trolling through the carefully quaint downtown area. Our stops always attracted gawkers and drew comments from those attracted by all the bikes. The tastiest eyeball candy seemed to be the Drifter, with its cherry-red paint and swooping fenders. The A.C.E. and Volusia also drew many positive comments. Other motorcyclists seemed most drawn to the Harley because it was new and because its styling evokes the dominant Harley dirttrack racers. The least-looked-at bike was the Vulcan 750. The Intruder, Marauder and Spirit also received lukewarm receptions and low scores for finish and appearance from our testers and others.

To keep prices down to levels that are acceptable in this class, the makers have had to find some savings. These bikes have about as many parts as the big twins do, so there aren't any savings there. The most obvious cost savings are in materials. Having genuine steel parts apparently isn't as important an issue in this class as it is with the big twins, so all the bikes, except the 883, VN750 and Intruder (which have long since amortized the tooling for their components), have plastic fenders. Though you can see a few other signs of corner cutting, they aren't obtrusive or extensive. Many sidewalk commentators thought the Drifter was an expensive, semi-luxury machine based on its finish and style. The amortization factor also permits the Vulcan 750 to deliver an impressive collection of features (see the Kawasaki capsule).

Changing Direction

When we gave up on seeing a break in the coastal stratus clouds, we decided to strike out east to California's Central Valley in search of photo opportunities. The back road we took out of Cambria is a tight, narrow little ribbon of bumpy asphalt that climbs and plunges through the coastal hills and has a notorious reputation for bringing down unwary riders. It was an excellent test for the handling capabilities of our three-quarter-dozen middleweights.

To negotiate this sort of road at a brisk pace, a bike needs a variety of qualities: responsive steering, well-controlled suspension, stability, cornering clearance, a handlebar bend and a riding position that provide control and strong, controllable brakes. None of the nine bikes performed strongly in all these categories, but each had some strength.

The Harley offers a great riding position for attacking curving pavement with its low, narrow handlebar and mid-set footpeg position. It also has excellent cornering clearance, thanks to an elevated undercarriage, a short wheelbase (a shorter wheelbase means that a motorcycle doesn't have to lean as far to ride a given arc at a given speed) and taut suspension (which means it doesn't compress as much in corners). Finally, it has the most responsive steering geometry with less front-wheel trail and a steeper steering-head angle than any of the other bikes. These ingredients mean that it turns quickly with low effort and can lean a relatively long way before the footpegs rub the road. On a smooth road it is also relatively stable while leaned over, though the stiff suspension unsettles it when the surface is bumpy. The more abrupt the bump, the more the 883R gets bounced around.

Honda's A.C.E. provides a more relaxed, upright position, with a mild rise to its 33.4-inch-wide handlebar. Its pegs are set lower and farther forward. The wheelbase is over three inches longer, and the steering head is raked out more and couples to more front-wheel trail, all of which point to slower, more stable handling, which is what you get. The bike feels bigger and more ponderous than the Harley and drags earlier, because it is wider and rides lower, but the wide handlebar gives good leverage and control, making steering very manageable. The suspension is softer and has less travel than the 883R, but the rates are well selected and it works respectably whether the pavement is smooth or lumpy.

The Spirit rides lower and drags sooner than the bulkier-looking A.C.E., in part because the Spirit's wheelbase is slightly longer. It has slightly less suspension travel and doesn't soak up bumps quite as well as the A.C.E. There were mixed feelings about its riding position and handlebar, which some riders liked more and some less than the A.C.E. arrangement. It seemed to steer a bit more responsively for most riders than the A.C.E., perhaps because it's slightly lighter and has less trail. Both A.C.E. and Spirit were hit for vague feedback while cornering.

Most riders rated the Drifter's handling as better than the Classic's, which is a bit of a puzzle, since the two Kawasakis have virtually identical chassis dimensions. It is likely that the Drifter's riding position provides a greater sense of control for many riders, although its floorboards drag at a slightly shallower lean angle than the Classic's pegs. The Drifter also carries an additional 30 pounds. The 800 K-bikes were rated behind the A.C.E. but ahead of the Spirit, with suspension action closer to the A.C.E.'s.

Despite somewhat slushy suspension, the Vulcan VN750 impressed most riders in fast, smooth corners thanks to its considerable clearance when leaned over, stability and responsive, linear steering.

Suzuki's two older bikes, the Intruder and Marauder, were at the bottom of the handling rankings. The pullback bar and geometry that resists turning more than the others hurt the Intruder, as did poorly damped suspension and a flexible feeling in fast corners. It wasn't very stable either. The Marauder saw similar complaints, although the suspension was slightly better. The two also were roundly criticized for ground-clearance problems. Not only do they drag fairly early, but the parts that drag are solid and will lever the front wheel off the ground if you press the issue. The Volusia ended up right in the middle of the pack in terms of handling. Riders wished for a little better steering response and feedback, and some thought it wasn't as stable as some of the others. Ground clearance was about average.

Braking was generally well received. Only the Intruder, which has a bit less front-wheel stopping power than the others and dives significantly under braking, saw any criticism. The VN750 also dives, but not as hard, and it has a strong dual disc brake on the front. The rest all gave sufficient power and control and were stable during hard stops. The Harley brakes demand the most pressure and a longish reach to the front brake lever. The A.C.E., Drifter, Marauder and Volusia have front brake levers that permit you to adjust their position, which can be a boon for smaller hands.

Buying In

Price is clearly a bigger issue in this class than for open bikes, and the prices of these bikes make them bargains when you compare them to their open-class brethren. It will cost you $5999 to buy the most affordable bikes here, the Marauder and Spirit, and $1500 more for the priciest, Kawasaki's Drifter. Despite tax, license and insurance, you can predict that some features will save money. The shaft drives of the Vulcan 750, Intruder and Volusia mean you will never have to replace chains and sprockets, which will probably more than make up for the extra initial cash (about $500) you fork out to get the shaft. Like Harley's belt, it will also save the mess of lubing a chain. Cast wheels mean you will never have to tighten spokes or true wheels, and the hydraulic valve adjusters of the Vulcan 750 and Harley prevent you from ever paying for a valve adjustment (which will include the cost of shims for the Kawasaki 800s).

In terms of reliability, we aren't aware of any persistent problems with any of these bikes, although we did have a couple of electrical problems. The Intruder's positive lead from the battery came loose, causing a miss, the source of which we couldn't identify until we rode it at night. Because the battery is located under the swingarm, reaching it to fix the problem was somewhat aggravating. The VN750 was sometimes reluctant to turn the engine over with the electric starter. Kawasaki says it was likely a bad ground for the battery or starter.

When testers were asked to rank these machines without considering price, the Volusia narrowly beat the Drifter as the favorite. "After this trip, I actually want one," said one rider of the Volusia. "Think of it as getting an 1100 for an 800cc price," said another. "It's the only bike here that has it all," was another comment. The Volusia had an even bigger lead when riders were asked to rate "Price vs. Package." With the Volusia, Suzuki has raised the bar (but not the price tag) in the 800-cruiser class.

Of the Drifter, its backers said: "Classy, well-assembled package, superb fit and finish and a good spread of power that would open my wallet," and "An all-around good motorcycle with excellent style." Of course, if we'd had to accommodate passengers, the Drifter would have scored much lower. When asked to rank the bikes with price factored in, the ranking for the Drifter, the most expensive bike here, dropped to an average of third behind the A.C.E., though two riders still rated it as their top pick.

Next in the money-is-no-object ranking came the A.C.E. and Classic, which tied for third. However, when price was factored in, the A.C.E. climbed to second, while the Classic fell to fifth, tied with the Intruder.

The Vulcan 750 scored a surprising fifth place overall, and one rider even listed it as his top pick. With price considered, it climbed a notch to fourth. The Spirit and Intruder fell in line behind it. The Spirit had the widest range of ratings, getting both a first and last with price referenced, so it may bear more consideration than its rating suggests, particularly if you are shorter of inseam.

The Harley wound up in eighth. "It's not a cruiser," commented one rider, "and it lacks the comfort and relaxed attitude of the rest." "Not a bike I'd buy as my only bike, but something I'd enjoy having in my garage," said another.

No one had much to say about the Marauder--they just gave it low marks, putting it in last place.

Gr8 Rides!

One guest rider, a relative newcomer to motorcycling with just a year's experience, offered some interesting observations about the 800s. At 6'3" and over 300 pounds, he had assumed he needed lots of displacement to find happiness on a cruiser. "I had severe reservations about the comfort of any middleweight motorcycle. Had I known the qualities and capabilities of these machines, I might have made quite different decisions about my choice of motorcycle. Now I know I can enjoy the lighter weight, low prices and versatility that these 800s offer."

Many riders have similar misconceptions about these middleweights. The elitism of big-bike owners, the profit motive of salesmen and a mistaken belief that bigger is automatically better make many buyers overlook the 800 class in favor of bikes with twice the displacement. Instead of getting a bike that is more capable, these big-bike buyers may miss smaller-displacement V-twins that perform as well and are easier to handle, more fun to ride and certainly much better bargains. We think the Volusia delivers the greatest capability in this class and the best deal among middleweights, and perhaps in cruising, but the range of bikes here can titillate a variety of taste buds.

RATINGS BY RIDER (5.0 Maximum)

Brasfield - Cherney - Elvidge - Friedman

Harley XL883R 2.5 - 3.0 - 2.0 - 3.5

Honda ACE 750 3.5 - 4.0 - 4.0 - 3.0

Honda Spirit 750 3.5 - 3.5 - 3.0 - 2.0

Kaw. Vulcan 750 3.0 - 3.5 - 3.5 - 2.5

Kaw. Vulcan Classic 4.0 - 3.0 - 3.5 - 3.5

Kaw. Vulcan Drifter 4.5 - 4.5 - 4.0 - 3.5

Suzuki Intruder 3.0 - 3.5 - 3.0 - 3.0

Suzuki Marauder 2.5 - 3.0 - 2.0 - 2.0

Suzuki Volusia 4.0 - 4.0 - 4.0 - 4.5

THE BIKES IN DETAIL

Harley-Davidson XL 883R Sportster

Since its arrival in 1957, the Sportster has been a fixture in Harley dealer showrooms and American streets. Introduced with 883cc 44 years ago, it grew to 1000cc in the 1970s, but returned to the 883cc displacement when the aluminum top end was introduced in the mid 1980s. Since then, a larger version, now 1200cc, has been introduced and numerous improvements have been integrated. New variations have also been added, but the 883 version, the most traditional of Harleys, remains. It uses the same air-cooled 45-degree V-twin design as the original Sportster of '57 and remains undiluted by counterbalancers or overhead cams. A single carb feeds both cylinders. Though predictions of a modern replacement for the venerable design have been plentiful for years, the Sporty takes on 2002 with the same familiar drivetrain package, which includes five speeds, a chain-drive primary and a belt final drive.

For 2002, a new model, the XL 883R we included in our test, has been added to the 883 Sportster family. The new bike takes its cues from Harley's dominant XR750 dirttrack racers. Set on the standard twin-shock Sportster chassis with an identical 3.3-gallon fuel tank, the new bike distinguishes itself with a pretty two-into-one chrome exhaust system, dual disc brakes up front, a low racing-style handlebar with a 28-inch-high swept-back saddle to match, a blacked-out engine, air cleaner cover, oil tank and handlebar switches, and orange-and-black paint and graphics that mimic Harley team racers. A single instrument (an electronic speedo), 13-spoke cast wheels (a 19-incher and a 16-incher) and the standard small Sportster headlight and abbreviated fenders complete the look.

At $6695 (plus $180 shipping), the 883R isn't the most expensive 883, but it is $1000 more than the basic model. For buyers enamored by a look that so successfully evokes Harley's racers, that style will make it a bargain.

Harley Sportster 883R Specifications & Performance

Price: $6695 - Wet weight: 534 lbs - Engine: 883cc air-cooled OHV 45-degree V-twin, 2 valves per cylinder -Fuel capacity: 3.3 gal. - Fuel mileage: 43 mpg - 1/4 mile acceleration: 15.63 sec., 83.3 mph

Honda Shadow A.C.E. 750 and Shadow Spirit 750

By the mid 1980s, Honda looked as if it were poised to blanket the V-twin market with its range of Shadows, which extended from 500cc to 1100cc. But as those models grew long in the tooth and demand waned, the middleweight V-twin category was abandoned when the 800 Shadow was discontinued. However, as cruisers surged in popularity again in the 1990s, a new middleweight was obviously needed.

Instead of reviving the 800 Shadow engine (still used in the Pacific Coast), Honda pumped up the volume of the 583cc Shadow VLX, boring and stroking it to 745cc to create the Shadow American Classic Edition 750 in 1997. The resulting 52-degree V-twin follows the pattern of the VLX, with liquid cooling, three overhead-cam-operated valves (two intake, one exhaust) per cylinder and two 34mm carbs. The alternator was beefed up to provide more juice and flywheel effect, and an additional gearbox ratio gave it five speeds. Like the 600, it has a chain final drive. The bike rolls on wire-spoke wheels with tube-type tires (a 120/90-17 up front and a broad 170/80 in back), covered dual rear shocks and covered 41mm fork tubes. The front brake uses a two-piston caliper. As the name suggests, the styling has a classic American flavor, with a broad two-piece saddle; wide, deep fenders; a big headlight and a fat 3.7-gallon fuel tank. There were originally two versions of the A.C.E., but now only the Deluxe remains, though the price ranges from $5999 for basic black to $6499 for pearl colors, with points in between for pinstripes on black or two-tone.

For 2001, Honda added the Shadow Spirit 750 to the line. This is a lightly tweaked A.C.E. with shorter gearing and street-rod attitude. The Spirit brings new styling cues including chopped fenders, a skinny 100/80-19 front tire on a wire-spoke wheel, an uncovered fork crowned with a small headlight, a lower and narrower handlebar, a leaner-looking 3.6-gallon fuel tank, a trimmer one-piece saddle that helps lower saddle height by an inch to 26.6 inches, exposed-spring rear shocks and a squat 160/80-15 rear tire. It is priced at $5999 regardless of color.

Honda ACE 750 Specifications & Performance

Price: $5999 - Wet weight: 533 lbs. - Engine: 745cc liquid-cooled OHC 52-degree V-twin, 3 valves per cylinder - Fuel capacity: 3.7 gal. - Fuel mileage: 43.4 mpg - 1/4 mile acceleration: 15.56 sec., 82.1 mph

Honda Spirit 750 Specifications & Perfromance

Price: $5999 - Wet weight: 528 lbs. - Engine: 745cc liquid-cooled OHC 52-degree V-twin, 3 valves per cylinder - Fuel capacity: 3.6 gal. - Fuel mileage: 44.0 mpg - 1/4 mile acceleration: 14.83 sec., 86.7 mph

Kawasaki Vulcan 750, Vulcan 800 Classic, and Vulcan 800 Drifter

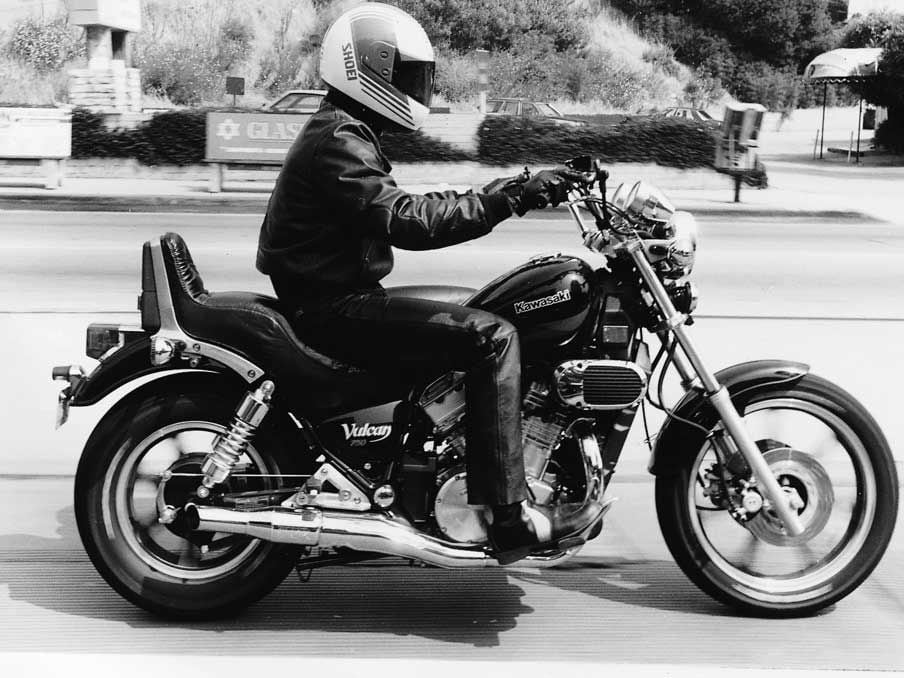

Kawasaki produces four middleweight Vulcan V-twin models, three of which we have included in this comparison. The 750 dates back to the mid 1980s. Though Kawasaki was late into the V-twin market, its 750 has endured as well as Suzuki's Intruder with fewer changes. Its style, particularly the liquid-cooled 749cc 55-degree V-twin engine, shows its age. That isn't all bad, however. Twenty years ago, the Japanese were competing to see who could pack the most features into their bikes. That means that the engine has eight valves with hydraulic adjustment to eliminate that chore and a gear-driven counterbalancer to smooth the V-twin's shakes, and it's tuned to rev and make strong power. The bike also offers a range of useful features unheard of on a modern cruiser, particularly a middleweight. Included in the $6099 price are a shaft final drive, a centerstand, a tachometer, a fuel gauge, four-way flashers, cast wheels with tubeless tires, air-adjustable rear shocks, dual front discs and a small passenger backrest. It lacks self-canceling signals, though.

The Vulcan 800 series uses the same basic engine architecture, including the 55-degree V angle, counterbalancer and 66.2mm stroke. However, the bore has been opened up to 88mm to give 805cc, compression has been softened and shim-type valve adjustment has replaced the hydraulics. In addition, a variety of changes, including a single 36mm carb instead of the 750's pair of 34mm mixers, have rearranged power characteristics to put more torque down low and leave less at higher rpm. Perhaps most important, the engine has been heavily restyled to create the appearance of a classic air-cooled V-twin instead of an obviously water-jacketed 750 engine. The rest of the 800 series was entirely new. Highlights included a single concealed rear shock, a longer wheelbase, wire wheels with tube-type tires, beefier 41mm (instead of 38mm) fork tubes, a wide 16-inch rear tire, placing the speedometer atop the bigger (4.0 vs. 3.6 gallons) fuel tank and replacing the shaft with a lighter, more efficient, messier, noisier and less expensive chain final drive with taller gearing.

The 800 range includes the Classic and Drifter models tested here. The 800A ($5999), which we elected not to include, is very similar to the Classic, with a 21-inch front wheel instead of the Classic's 16-incher, uncovered fork tubes, a smaller headlight and a higher, wider handlebar. All three share the same chassis, but the Drifter differs markedly from the Classic with its deeply valanced plastic fenders, patterned on the Indian style, two-into-one exhaust and solo saddle. This year, some of the classic touches of previous Drifters have been abandoned to give the Drifter a brighter, contemporary feel around its classic style. These include a candy-red color and bright chrome trim instead of black pieces.

Prices have come down on the 800s since we last rounded them up in 1997. The Classic at $6999 is $1000 less than it was then, and the Vulcan 750 has shed $500 from its price. However, the 800 Drifter remains the priciest of this group at $7499.

Kawasaki 750 Vulcan Speciifcations & PerformancePrice: 6099 - Wet weight: 544 lbs. - Engine: 749cc liquid-cooled DOHC 55-degree V-twin, 4 valves per cylinder - Fuel capacity: 3.6 gal. - Fuel mileage: 46.1 mpg - 1/4 mile acceleration: 13.98 sec., 93.1 mph

Kawasaki Vulcan 800 Classic Specifications & PerformancePrice: $6999 - Wet weight: 575 lbs. - Engine: 805cc liquid-cooled SOHC 55-degree V-twin, 4 valves per cylinder - Fuel capacity: 4.0 gal. - Fuel mileage: 44.6 mpg - 1/4 mile acceleration: 14.34 sec., 89.9 mph

Kawasaki Vulcan 800 Drifter Specifications & PerformancePrice: $7499 - Wet weight: 599 lbs. - Engine: 805cc liquid-cooled SOHC 55-degree V-twin, 4 valves per cylinder - Fuel capacity: 4.0 gal. - Fuel mileage: 46.1 mpg - 1/4 mile acceleration: 14.56 sec., 88.9 mph

Suzuki Intruder 800, Marauder, and Volusia

Suzuki's line of middleweight V-twin cruisers traces its roots to the 1985 Intruder 700. Honda and Yamaha already had 700 V-twins (the displacement was created to keep them under the engine size subject to a tariff created to protect Harley in the 1980s) on the market in 1985. However, the Intruder, with its trim, aggressive lines and obvious custom/chopper influence, was the most radical of that generation of Japanese cruisers. The Intruder evolved, growing to 750cc when the Harley tariff was rescinded in 1988, then to its current 805cc in 1992. Though most of its competitors from the mid 1980s have disappeared, the Intruder has soldiered on. Its success can be attributed to its distinctive and well-executed styling and its power. The Intruder 800 outruns all comers in this class and many V-twins twice its size.

With its 21-inch wire-spoke front wheel, pullback handlebar and chopperesque style, the Intruder's look wasn't for everyone. So in 1997, Suzuki introduced the Marauder. It has the same basic 45-degree liquid-cooled single-overhead-cam engine with four valves per cylinder and offset crankpins to cancel vibration, and it uses a five-speed like the Intruder's. However, the Marauder has chain final drive instead of the Intruder's shaft drive, which lowers the price substantially. It also brought street-rod styling to the Suzuki cruiser line, with a shorter front end with inverted fork legs; cast wheels with wider, smaller-diameter tubeless tires; a longer wheelbase and a wider saddle. All the major pieces as well as the details have been restyled. Despite its speedy-looking styling, the Marauder is actually slower than the Intruder, but it's also less expensive at $5999 compared to the Intruder's $6399.

The problem with those two 800s was that neither one really suggested leisurely trolling or long weekends in the saddle. So this year, Suzuki rolled out another 805cc V-twin, the Volusia. Though the name sounds like something unpleasant, it's actually taken from the Florida county where Daytona Beach, site of our biggest motorcycle event, is located. Styled along classic American lines, the Volusia has the same extended wheelbase as the Marauder, but offers substantially more room for rider and passenger and a broader seat as well. A bigger (4.2 gallons versus 3.4 for the Marauder) fuel tank provides more range to enjoy the cushier Volusia layout and complements the full-fender, covered-fork style of the bike. The speedometer, which includes an LCD fuel gauge/odometer/tripmeter/clock, is mounted atop the tank. It uses a shaft for final drive with wire-spoke wheels and fat tube-type tires, and both body and engine have again been completely restyled. The fenders are deep and wide, and the crankcases have been filled out to make the engine look larger. The Volusia ($6599) is often mistaken for an 1100-or-larger motorcycle because of its size.

Suzuki Intruder 800 Specifications & Performance

Price: $6399 - Wet weight: 477 lbs. - Engine: 805cc liquid-cooled SOHC 45-degree V-twin, 4 valves per cylinder - Fuel capacity: 3.2 gal. - Fuel mileage: 44.6 mpg - 1/4 mile acceleration: 13.74 sec., 79.2 mph

Suzuki Marauder 800 Specifications & Performance

Price: $5999 - Wet weight: 482 lbs. - Engine: 805cc liquid-cooled SOHC 45-degree V-twin, 4 valves per cylinder - Fuel capacity: 3.4 gal. - Fuel mileage: 43.9 mpg - 1/4 mile acceleration: 14.46 sec., 88.1 mph

Suzuki Intruder Volusia 800 Specifications & Performance

Price: $6599 - Wet weight: 587 lbs. - Engine: 805cc liquid-cooled SOHC 45-degree V-twin, 4 valves per cylinder - Fuel capacity: 4.2 gal. - Fuel mileage: 38.9 mpg - 1/4 mile acceleration: 15.34 sec., 83.5 mph

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/H6Z2IC7WYRBXZNQS4MI3SZ5KPQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IWO5T5PBT5E4HFQ5GK47H5YXR4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OQVCJOABCFC5NBEF2KIGRCV3XA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/F3O2DGLA4ZBDJGNVV6T2IUTWK4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZXYQE3MHLFDSPKNGWL7ER5WJ4U.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/RDF24VM7WVCOBPIR3V3R4KS63U.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/W7RSIBFISNHJLIJESSWTEBTZRQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/AERA26ENRNBW3K324YWCPEXYKM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/YWX3YX7QBBHFXFDMEEEKRG4XJE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/I7OKI53SZNDOBD2QPXV5VW4AR4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IH52EK3ZYZEDRD3HI3QAYOQOQY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/K2FSAN7OWNAXRJBY32DMVINA44.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4XK7JL24FCUTKLZWUFVXOSOGE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/JJNXVAC27ZCDDCMTHTQZTHO55Y.jpg)